I wrote this for my final term paper in college so its formatted very formally among other things

Abstract

The restricted access to academic literature has been a topic of debate for the past three decades. With the advent of the internet and all journals going digital, the business model and revenues changing, the ethicality of these big publishing houses have been questioned from time to time. In this paper, I try to analyze the economics, usefulness, and ethicality of publishing houses and present claims for unrestricted access to academic literature.

Methodology

The primary sources used are studies, research, and news articles which came in the wake of the Open Access Movement. It also features Aaron Swartz’s Guerilla Open Access Manifesto which was one of the founding works of literature on the modern iteration of the movement.

Introduction

Academic publishing is the subset of the publishing industry which deals with distributing academic research. The modern era of academic publishing started when the British government paired Butterworth’s (traditional British publisher) with Springer (German academic publisher) to increase the quality of scientific journals for being inefficient and broke. From their, Robert Maxwell took over the project in 1951 and turned academic publishing in a money-printing machine. [1]

For a field as niche as this, readers might be surprised that the profit margins of these publishing houses rival that of tech giants. In 2010, Elsevier’s (old academic publishing house) scientific publishing arm reported profits of £724m on just over £2bn in revenue. It was a 36% margin – higher than Apple, Google or Amazon posted that year. [1] Despite all this, usually a total of $0 is given to the author of the research. The prices only have increased despite the cost involved in going down with the internet boom. This raises a few clear cut questions about the morality of these academic publishing houses and should they even exist in the first place? This paper explores these questions and tries to present Open Access as a solution to the problems in the existing academic publishing system.

The dirty economics of Academic Publishing

Today, the majority of academic research is funded with government grants to the researchers and institutions and if you want to read the research paper that you funded with your tax paying money, you still need to shell out big bucks. On Elsevier, accessing just the introduction of a book or a single paper for 24 hours costs $31.50, purchasing one article from a maths journal from 1982 costs me $55.20 , buying a subscription to a full journal in India can cost anywhere from $5000 to $40,000[2] and accessing the whole Elsevier library can cost up to $9M per year [3] with the clear being the California state university which pays ~$11M for the access. These prices are pretty much the same among the big players with pay per view costing around $37 on Taylor and Francis, ~$38.50 on Springer, and $42 on Wiley-Blackwell. Scholars, academics, and institutions are forced to pay this staggering price if they want to keep

up with a field of research. In 2013, this made the academic publishing industry over $25Bn with most of the revenue coming from developed places like the US (55%) and Europe (28%) while Asia which has the majority of student scholars only having 14% share in the revenue.[4] These aforementioned publishing houses also regularly profit margins of around 40% per year. To put this in context, the net profit margin of Facebook is 28.57% [5], Google is 20.71% [6], Apple is 21.35% [7], Amazon is 3.56%[8] and Pfizer (biggest pharma company) is 31.71% [9].

If you take a look at the business models of most non-academic publishing companies, let’s say the Penguin Random House, they first acquire content, pay the author an advance for the content, then pay editors for proofreading/finalizing the article and then pay platforms for distribution and then pay the author royalties for every copy sold after a certain number of copies. With this model, Penguin Random House or any typical publishing company makes somewhere around 12-15% of the profit. But in the case of Academic publishing, the publishing company can avoid the majority of these investments as they don’t have to pay the author ever which means no royalties as they are already paid by the public grant and the peer review process is done by scientists on a voluntary basis and is also proven to be a scam many times with authors peer-reviewing their own papers or getting fake reviews from a circle of “friends” which make the paper look legitimate.[10] .. With the paper printed journals back in the day, when you had to transport each print to the reader there were significant distribution costs, but with the advent of the internet, the companies can duck all distribution costs as all they have to do is upload it onto the internet. With no printing cost, and distribution infinitesimally cheap, one would think that the cost of these papers and journals would have dropped down after the internet boom but with an effective monopoly over the market lobbying, they have managed to keep the prices up, even increasing exponentially. A quick look at numbers shows that the subscription prices have risen by about 145% in the last 6 years. [11]

A 2015 study [12] by the School of Library and Information Sciences of University of Montreal, showed that in 2013, the top 5 academic publishers, publish more than 50% papers in every subject with Elsevier, Springer, Wiley-Blackwell and Taylor and Francis making frequent appearances on the list. This creates virtually no competition in the market which could have potentially dropped the price down. This pricing crisis has killed nearly all of the individual subscriptions, so the only way left to access them are university and public libraries. But with skyrocketing prices, even big affluent universities like Harvard can’t afford to foot the $3.5M bill put on their library every year by these large publishers. The only solution is to not subscribe to a bunch of journals which creates a huge access gap for the patrons of the library and hinders research. These access gaps are worse in developing or poor nations. In 2008, Harvard subscribed to 98,900 serials and Yale to 73,900. The best-funded research library in India, at the Indian Institute of Science, subscribed to 10,600. Several sub-Saharan African university libraries subscribed to zero, offering their patrons access to no conventional journals except those donated by publishers.[13] A lot of these publishers also bundle less popular/read journals with the more popular/read journals so you can’t just unsubscribe from these fewer read journals without potentially depriving readers of those popular journals. All in all, it is a system designed to yank as much money as possible from the consumer. Publishing houses often say point out that they add value in the literature which is true to some extent, but the author, editor and the funder (public) add much more value than the publishing house does and two (author and editor) of them don’t get paid and another one (public) has to pay to access it while publisher gets the majority of the cream.

What is open access and why open access?

Open access here basically means free unrestricted access to publicly funded research. This means that researchers post the papers directly on a free database such as arXiv instead of going through big publishing houses. OA isn’t an attempt to bypass peer review. Publishing houses generally don’t pay for peer review editors as most of it is done by dedicated volunteers for their own curiosity and interest, the editors still have the same incentive when a journal turns OA as they had before. OA also doesn’t reduce the rights of the author over their work. It in fact gives more freedom to the author as can choose between various Open Access/Open Source licenses and see which one works best for their interests, all of which have safeguards against plagiarism and require author attribution. [14]

OA is the part of the solution to many aforementioned problems. It removes the barriers of entry so that people who can’t afford to go to financially affluent institutions can access this critical literature. In the words of Aaron Swartz, a hacktivist who fought for OA and gave his life for the movement, “Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allowing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable.”^ [15]

OA completely solves the pricing crises which has been plaguing the academic world for decades now but even if we had no pressing issues in our hand, we ideally should want to take full advantage of the internet for the progress of academic and try to weed business out of it. The latest argument for open access came about with the pandemic when researchers are finding it hard to get access to the millions of paywalled coronavirus related papers and studies which can potentially help in saving millions of lives.

Open access has a greater impact

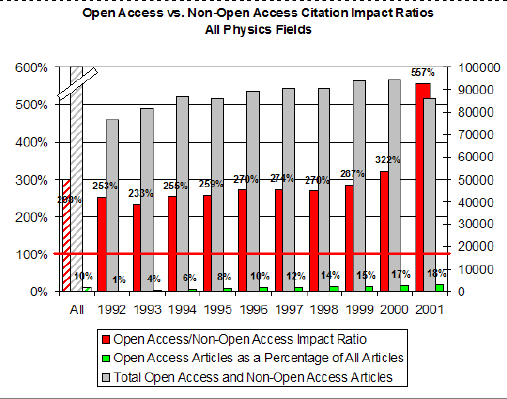

Studies have shown that open access research has a greater impact on the scientific community than its proprietary counterparts. Talking about physics, which was one of the first fields to adopt OA in the form of arxiv.org, In 1991, OA works were only 1% of the total published works were cited about two times more than that 99 % paid articles. The percentage of OA works in the field increased to 18% in 2001 when they cited ~5.5 times more than Non OA works. [16]

In the field of computer science, an analysis of 119,924 articles in 2001 showed that

the mean number of citations to online (free) articles is 7.03 while the mean number

of citations to offline (paid) articles is 7.03. [17]

In the field of computer science, an analysis of 119,924 articles in 2001 showed that

the mean number of citations to online (free) articles is 7.03 while the mean number

of citations to offline (paid) articles is 7.03. [17]

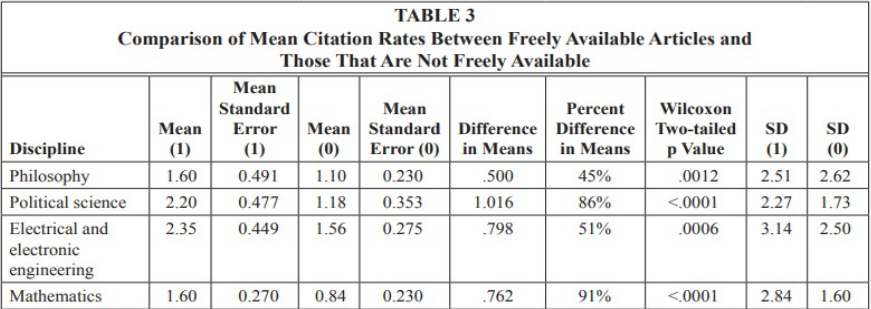

Kristen Antelman expanded this study to all fields in her paper “ Do Open-Access Articles Have a Greater Research Impact?” and found that the even though the percentage of OA papers is only 17% in philosophy, 29% in political science, 37% in Electronical engineering, the mean citations of OA papers in all these fields is greater than the mean citations of non OA papers. [18]

OA gives free and easy access to academic literature as it is easily indexed by search

engines like Google and ResearchGate.

The publishing industry also exerts too much influence over what scientists choose to

study. All they need is a steady stream of paper which has a broad audience. They do

not want researchers exploring dead ends and niche topics that are not interesting to

the general public which in the long run are very important to the development of the

field. [19]. This results in headlines like “Eating popcorn increases your confidence” but

the drug trial studies don’t get published. [20]

OA gives free and easy access to academic literature as it is easily indexed by search

engines like Google and ResearchGate.

The publishing industry also exerts too much influence over what scientists choose to

study. All they need is a steady stream of paper which has a broad audience. They do

not want researchers exploring dead ends and niche topics that are not interesting to

the general public which in the long run are very important to the development of the

field. [19]. This results in headlines like “Eating popcorn increases your confidence” but

the drug trial studies don’t get published. [20]

Conclusion

Publishing houses that were originally started with the intention of making academia accessible to scholars and researchers have become the real villains of the industry by keeping the publicly funded research from the people who funded it. The business model on which they function has vanished in the past 3 decades but they have somehow still survived by constant lobbying. We’re past time of damage control and into the era, we are seeing consequences with the inaccessibility of related papers this pandemic being the latest case. Scholars create knowledge by sacrificing their time, money, and labor and there is no reason to give its access to multi-billion dollar corporations. The current system is immoral and inefficient as it has zero interest in taking advantage of our collective intelligence. It should be our moral imperative to share the literature with people not privileged enough to afford the humongous costs associated with it. So to promote science, we should adopt Open Access as a means of scientific communication.

References :

-

(Buranyi, S., 2017. Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science?. Gaurdian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science [Accessed 1 June 2020].)

-

(https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals/journal-pricing/print-price-list)

-

Bergstrom, Theodore C et al. “Evaluating big deal journal bundles.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 111,26 (2014):9425-30. doi:10.1073/pnas.

-

Ware, M.; Mabe, M. The STM Report: An Overview of Scientific and Scholarly Journal Publishing; International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015.

-

“Facebook Profit Margin 2009-2020: FB.” Macrotrends, http://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/FB/facebook/profit-margins. [Accessed 1 June 2020]

-

“Google Profit Margin 2009-2020: FB.” Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/GOOG/alphabet/profit-margins [Accessed 1 June 2020]

-

“Apple Profit Margin 2009-2020: FB.” Macrotrends,https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AAPL/apple/profit-margins. [Accessed1 June 2020]

-

“Amazon Profit Margin 2009-2020: FB.” Macrotrends, (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AMZN/amazon/profit-margins). [Accessed 1 June2020]

-

“Pfizer Profit Margin 2009-2020: FB.” Macrotrends,(https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/PFE/pfizer/profit-margins). [Accessed 1 June 2020]

-

Ferguson, C., Marcus, A. & Oransky, I., 2014. Publishing: The peer-review scam. [Online] Available at: https://www.nature.com/news/publishing-the-peer-review-scam-1.16400[Accessed May 2020].

-

iansample, 2012. Harvard University says it can’t afford journal publishers’ prices. Gaurdian [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/24/harvard-university- journal-publishers-prices [Accessed May 2020].

-

Larivière V, Haustein S, Mongeon P (2015) The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers inhe Digital Era. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.

-

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. (p.44)

-

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. (p.46)

-

Swartz, Aaron Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. Retrieved from http://cryptome.org/ 2013/01/swartz-open-access.htm [Accessed May 2020]

-

Stevan Harnad and Tim Brody, “Comparing the Impact of Open Access (OA) vs. Non-OA Articles in the Same Journals,” D-Lib Magazine 10 (June 2004). http://www.dlib.org/dlib/june04/harnad/06harnad.html.

-

Lawrence, S. Free online availability substantially increases a paper’s impact. Nature 411, 521 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/

-

Antelman, K. (2004). Do Open-Access Articles Have a Greater Research Impact? College & Research Libraries, 65(5), 372–382. doi: 10.5860/crl.65.5.

-

(Buranyi, S., 2017. Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science?. Gaurdian, [online] Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-scienhce [Accessed 1 June 2020].)

- Lane, S, 2013.Why the data on all drug trials must be released. Guardian, [online] Available at :https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/sep/17/drug-trials-data-released[Accessed 31 May 2020]